Anglo-Saxon Romsey

The Evidence in the Landscape

The Anglo-Saxon Barrow Cemetery on Breach Down, Kent

Anglo-Saxon buckles and jewellery found at Breach Down, now in the British Museum.

Illustration by Lord Albert Conyngham of artefacts found during his excavation of barrows on Breach Down in 1841, published in Archaeologia XXX, 1844. Most of these objects can be identified in the British Museum’s collections.

The First General Meeting of the British Archaeological Association was held at Canterbury in September 1844. It included an excursion to view the opening of Saxon barrows in the park of the new association’s President, Lord Albert Conyngham, at Breach Down. The illustration, published the following year, gives a good indication of the weather, but not of the participants - around 200 ladies and gentlemen viewed the excavations while sheltering under their umbrellas from the rain. The finds from the eight barrows opened that day included knives, spearheads, shield bosses, beads and, in the burial of a child, toys,' the evident offerings of parental affection'. Conyngham opened a further eight barrows on Breach Down the following week. The finds made by Conyngham were later purchased by the British Museum, at which time he was known as Lord Londesborough.

During the final year of my course in Early Medieval Archaeology at UCL I wrote a dissertation on the finds from Breach Down in the British Museum. I am now preparing a report based on the dissertation and my subsequent research. The photos and the drawings of the finds all date from 1977. I am continuing to update the inventory and catalogue. PDFs of the work so far are available for:

Changing views of Breach Down - 1840 to 1977.

Grave-goods

The grave-goods recovered from the barrows on Breach Down date the majority of the burials to the 7th century, with the cemetery possibly continuing in use into the early 8th century. The range of artefacts is typical of the rich cemeteries in East Kent. Jewellery includes a garnet disc brooch, a gold bracteate and a gold disc pendant decorated with a cross. Three copper-alloy cross pendants and a pin with a cross head suggest their owners were Christians. A mounted bird’s claw and a cowrie shell were amulets, an indication of continuing pagan practices or unease with the new religion. Drop-shaped amethyst beads were found in several graves, including one with a necklace of 18 beads - one of the largest number of amethyst beads in any single Anglo-Saxon burial. There were also two globular crystal beads, many glass beads and some amber beads. A set of linked pins, two pins joined by a chain, is a 7th-century female fashion accessory, as are the two girdle hangers or chatelains. Silver wire rings, mainly used as components of a necklace, were common throughout the 7th and into the 8th century.

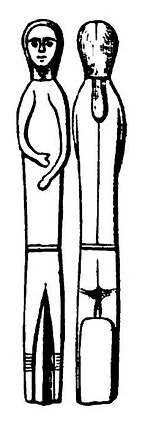

Human figurine amulet

The little copper-alloy figure of a man (E1), 5.5 cm in length, is the most enigmatic object that was found on Breach Down. It was exhibited at a meeting of the British Archaeological Association in 1848 and was said to have been picked up near the tumuli. It had probably been overlooked during the excavation of one of the barrows. His eyes were drilled after casting and, when found, were filled with ‘red stone or paste’, probably glass or enamel. A rather idealised illustration from 1848 seems to show him wearing a hood. This interpretation ignores the detail that shows his hairstyle - his hair is parted down the middle and lies flat against his head and he appears to have a ponytail. The head is separate from the body - the figurine has been described as a pin and sheath, used as an amulet or possibly a phial containing a liquid or medicine. It is actually in two pieces because it was damaged, and repaired, in antiquity. A hollow in the neck was probably a casting fault, a gas bubble in the metal. The head broke off and was reattached to the body with a metal dowel.

There are several cast metal figures that are similar in date and appearance to the one from Breach Down. The two female figurines were found in Suffolk, b. at Halesworth and c. at Eyke. (Lisa Brundle (2020) Exposed and Concealed Bodies: Exploring the Body as Subject in Metalwork and Text in 7th-Century Anglo-Saxon England, Medieval Archaeology, 64:2, Fig. 7). One has a ponytail like the male figure from Breach Down. The other is described in the article as wearing a pleated skirt and ‘a long veil that falls to the feet’. Could this be long hair hanging down her back? In 1839 a preserved head of hair was discovered inside a lead coffin beneath the floor of Romsey Abbey. The sex of the person has not been determined, but the burial has been radiocarbon dated to 895-1123 - late Saxon or early Norman. The individual had long, plaited hair.

The presence of a suspension loop on the little man from Carlton Colville, Suffolk shows that it was made as a pendant. It is made of silver and partially gilded, but looks an unlikely piece of jewellery, more probably an amulet. Recent research has identified the Cerne Abbas Giant as a Saxon depiction of Hercules. In their paper on ‘The Cerne Giant in its Early Medieval Context’ authors Thomas Morcom and Helen Gittos compared the ‘tear drop’ face of the giant with the Carlton Colville figure, the man on the Finglesham buckle and the face on the Sutton Hoo sceptre. The Breach Down man with his round eyes is a closer match.

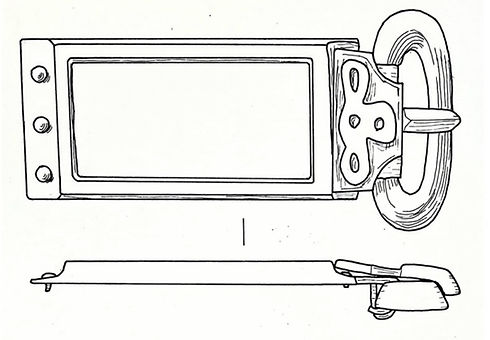

Buckles

Folded-plate buckles

Buckles were one of the most common grave finds at Breach Down. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes, employing a number of different methods of construction. This is a result of both function and fashion - they were made to serve different uses and, as decorative objects, to reflect the individual taste and status, and possibly the religion, of their owners. The most common type of buckle was made up with a plate of folded sheet metal, secured to the strap or belt by two or more rivets along the base and having a cast loop and a simple tongue made from a piece of wire.

Buckles with folded plates - B4, L3 & L1. The smaller two have plates under 1 cm in width.

There are two large buckles from Breach Down with a folded plate construction, both with double tongues. The end of the plate of B5 has been trimmed to a similar pattern to the small buckle L3 and is decorated on the edges and on the loop. The plate is 5 cm in width and with its elongated, narrow loop, would have been used on a wide belt. The rounded plate of buckle M1 was heavily tinned to give it the appearance of silver. The loops and tongues of the two buckles were cast.

Cast-in-one buckles

The finds from Breach Down include examples of a type of decorative buckle that were made with the plate and loop cast in one piece. All that was required to complete the buckle was the addition of a simple wire tongue and, in certain cases, the drilling of the fixing tabs. Openwork designs were present in the casting; punched and engraved ornamentation was often added as an embellishment. Although simple in concept, one can imagine that the preparation of the moulds and execution of the casting required a great deal of skill on the part of the metalworker. The method encouraged the production of a wide variety of buckle shapes employing different decorative schemes. Often the influence of the more complex and expensive buckle types is evident. Buckles with openwork decoration have been found in graves of both sexes and with children, most of which were sparsely furnished. This paucity of grave goods reflects the growing influence of Christianity at the period in which these buckles were use, in the late 7th century.

Buckle L9 has a square plate, most of which is taken up by three long, sub-rectangular cut-outs which provide the only decoration. There is no differentiation between the plate and loop, both of which are rather crudely shaped. In contrast, L10 is a more carefully executed buckle, neatly shaped and pierced and with punched decoration added to it. It was found in a man’s grave (Barrow 15) along with a sword, spearhead and shield boss. It is too small to have been a belt buckle, only 2.7 cm in length, but might have been used on a sword harness. Buckle L11 has the basic rectangular form of the more complex and expensive buckles with separate rectangular plates. The rectangular shape has been extended at the base to give an extra flourish - here with two rounded projections where some examples have a pair of bird or animal heads. The openwork designs might have been backed with red fabric to imitate the garnets on richer buckles. The crosses might have been intended as Christian symbols. The buckle was the only object in the burial of ‘a very tall man’ (Barrow 78); it was attached to the remains of a leather belt that crumbled on exposure to the air.

L8 imitates the form of a triangular buckle with its outline including the positions of the three large bossed rivets. Lacking a tongue, it is not a buckle but half of a clasp - originally paired with a similar object with a hook in place of the loop. Two complete clasp sets from Taplow, decorated with Style II filigree, are of the same triangular form. The shape is also used on hinge L87, complete with three rivets.

Complex buckles

The larger, complex buckles were used as personal adornment, as a masculine form of jewellery. They display more complicated methods of construction than the folded-plate and cast-in-one buckles - and they would have cost more. Examples of the two main forms of buckle that were in fashion in the early 7th century were found at Breach Down, buckles with rectangular and triangular plates. These were made in imitation of the elaborate gold and garnet buckles found in the higher status burials in other cemeteries, borrowing elements of their designs but using cheaper materials in their manufacture.

Buckle L14 displays the classic features of the triangular buckles at the height of their popularity in the early 7th century. The components of the buckle were made from copper alloy and were cast - plate, rivets, loop and the tongue with its shield. The plate is made up of an open frame which holds a sheet of gilt metal with repoussé Style II decoration of a pair of intertwined animals. The three dome-headed rivets were cast complete with their beaded collars. The interlace and the collars imitate the filigree executed in plain and beaded gold wire on the richer buckles. The oval loop is attached to the plate by a rectangular extension on the front of the plate which is bent around the straight bar on the back of the loop. This has a slot in the centre for the tab on the back of the shield which is also bent around the back of the loop. The front edge of the plate is curved to fit in with the rounded base of the tongue shield. The oval loop is wider than the plate. It was tinned and would have had a silvery colour.

There is an additional, and rather difficult to spot, design element that has been copied from the higher status buckles. The frame in front of the rivets has been shaped to form a pair of forward-facing birds’ heads. One side appears to have been damaged or poorly cast, but on the other incised lines mark the lower curve of the beak and a lentoid eye. Bird heads with garnet settings are found in this position on silver-gilt buckles from Sarre grave 68, King’s Field Faversham and Wickhambreaux in Kent and Alton, Hampshire. Buckle L14 is unusual in having been found in a woman’s grave, Barrow 53. Its position in the grave, on the hip, indicates that it was on a belt when buried. It shows signs of wear and could have been fairly old, passed down to the woman from a male member of her family.

Triangular buckles with gold filigree panels of Style II interlace and garnet settings provided the models for the copper-alloy buckle from Breach Down. The buckle from Sarre grave 68 has the head of a bird with a cabochon garnet eye on the frame in front of the rivet. On the buckle from Alton a garnet setting forms the neck of each bird. The eye and the curved beak are defined by punched lines. The Alton buckle was damaged and repaired with strips of silver holding the panel in place.

The three bossed rivets with their beaded collars preserve the triangular shape of the great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo. The Style II bird heads on the shoulders of the buckle face away from the loop with their beaks curving around the outer edge of the rivets.

Another complex buckle from Breach Down shows a variation on the basic triangular buckle form. L12 is smaller than L14, only 5.3 cm in length, and its proportions make it appear rather dumpy in comparison. The buckle is made from copper alloy and was cast in three pieces. The plate is relatively wide and short with a pair of holes for the side rivets at about the centre of the buckle, much further back than on other triangular buckles. The tongue shield is positioned near these rivets, behind the loop rather than overlapping it. The position of the shield was made possible by the buckle’s construction. Rather than being attached to the loop, the shield is held by an iron pin which passes through the front edge of the plate and lugs at the back of the loop. A long tongue was then required to span the full width of the loop and, to keep it in proportion, it needed to be quite wide.

Perhaps the necessity for a large tongue encouraged the metalworker to model the tongue into the shape of a duck’s neck and head or, conversely, the position of the shield might have been determined to allow space for this extra feature.The tongue appears as a little 3-dimensional figure extending from the front of the shield and rising at an angle above the level of the buckle plate. The tongue shows signs of wear behind the collar at the back of the duck’s head. The modelling of the tongue in this way is very unusual. The buckle plate, shield and loop are decorated with punched ring-and-dots, a motif that was widely used on the metalwork found at Breach Down.

The method of construction of buckle L12 with the tongue and loop both swivelling on a pin was also used for the Sutton Hoo gold buckle. The corrosion of the iron pin has fixed the position of the loop and tongue on L12.

L64 is a simpler form of buckle which lacks a plate. A tab on the underside of the shield was bent around the straight bar on the back of the loop.

Although it is visually very plain, the triangular buckle M2 is elaborate in its construction. The triangular plate, oval loop and the three dome-headed rivets were all cast, made from copper alloy. The plate takes the basic form of a triangular buckle, with rounded protuberances for the forward pair of rivets and a disc at the apex for the larger rear rivet. The back plate is made of sheet metal and is the same shape as the plate, but slightly larger. Between the two plates is a folded sheet of metal holding the loop with a slot cut out for the tongue. The tongue is made from a piece of wire and is bent around the back of the loop. The buckle is undecorated - there are no collars on the rivets and no tongue shield. It is probably later in date than the more elaborate triangular buckles, dating from the second quarter of the 7th century, part of a trend towards cheaper, cast buckles.

Buckle L13 is an example of a style of buckle with a rectangular plate that was in fashion in the early 7th century. It was produced in imitation of one of the rich and elaborate buckles with the plate and shield decorated in gold and garnet. It is made from copper alloy and was cast in three pieces - tongue and shield, loop, and plate, which were each tinned to give them a silver colour. The plate is an open rectangular frame, recessed underneath to take a central panel. It has three small round-headed rivets at one end and two rivets underneath the tongue shield. The plate is attached to the oval loop by two forward projections of the plate which are bent around the straight bar on the back of the loop. The shield is decorated with a design of four loops which was probably set against a background of red enamel. A buckle from St Peter’s, Broadstairs grave 98 is so similar to L13 that it might have been cast in the same set of moulds. This buckle contains a gilt repoussé plate decorated with Style II ornament.

The high status rectangular buckles combine gold filigree interlace with gold and garnet cloisonné in intricate and inventive designs. The buckle from Rijnsburg in the Netherlands has a plate decorated with a panel of Style II interlaced animals executed in gold filigree. Interlace on the tongue shield is bordered by garnet cloisonné made up of small, interlocking, angular cells. In contrast, the buckle from Gilton Hill, Ash in Kent employs cloisonné as the basis for the decoration, using heart-shaped and rounded cells to enclose two fields of simple filigree interlace on the plate. Buckle L13 from Breach Down probably had a central panel on the plate with imitation Style II filigree, and the looped design on the shield might have been copied from a buckle with filigree on the shield. However, the design on the shield of the Gilton buckle of intersecting semicircular cells is suggestive of the looped design on the shield of L13. If this had been surrounded with red enamel then it is likely to have been based on a cloisonné model.

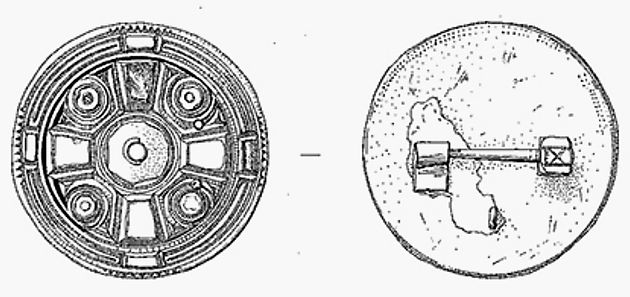

Jewellery

There is a small but interesting collection of jewellery from the burials on Breach Down. The most striking feature of these pieces is their use of Christian symbolism, an indication of the adoption of this new religion by the local community. The copper alloy cross-headed pin and pendant crosses, and the gold disc pendant are explicitly Christian. The arrangement of settings on the keystone garnet disc brooch can also be interpreted as a cross.

Only one brooch was found in the 100+ barrows excavated on Breach Down, the keystone garnet disc brooch L16. This type of brooch was developed in Kent during the second quarter of the 6th century following the adoption of the use of garnet settings and borders decorated with niello, techniques employed by Frankish metalworkers. These features were combined with chip-carved Style I animal ornament to produce a distinctive type of brooch. Keystone garnet disc brooches continued to be made well into the 7th century, still employing chip-carved decoration, sometimes of Style II animal ornament.

Brooch L16 was cast in silver and partially gilt. It is unusual in that most of the main field is taken up by the eight settings, four triangular garnets and four circular of white paste, which surround the central setting. A simple rectangular wedge separates the settings, each squeezed into the limited space available. Such a simple ornament merely served as a space filler between the settings which were obviously intended as the main decorative elements. The brooch was found in Barrow 53 along with the large triangular buckle L14 with the gilt Style II plate. Both objects were very worn - perhaps the woman was buried with her family’s heirlooms, her father’s buckle and her mother’s brooch.

The keystone garnet disc brooch from Ampfield has Style I decoration between the settings. There is more information about the brooch on the Economy - Routeways page.

The keystone garnet disc brooch from the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Winnall near Winchester is decorated with Style II interlace. A pair of birds of prey with curved beaks face each other at the four round settings. Their heads are similar to those on the triangular buckles from Breach Down and Alton.

The cross-head pin B1 has been described as a dress pin or a hairpin; either use would have been awkward. It is difficult to see how the weight of the pin could have been supported by either hair or fabric with such a relatively short, tapered shaft. It seems to have been more of a symbolic object representing the Christian beliefs of its owner. It was found in a woman’s grave, Barrow 103, buried at her side in a wooden box.

The head of the pin is basically a disc with circular cut-outs creating the curvilinear cross with expanded arms. Two projections indicate the ends of the lower arm which would complete a circular cross with arms of equal length. Instead, the lower arm extends into the narrow rectangle that forms the body of the pin, giving the pin the resemblance of a sculptural stone cross with its shaft. Contemporary gold and garnet pectoral crosses have similarly shaped arms with curved edges arranged around a central roundel. These don’t have circular spaces between the arms, an element of the design that appears to relate the pin to sculptural crosses. However, the resemblance is likely to be coincidental. It is difficult to see how this object could have been used as a personal ornament or dress accessory. An alternative interpretation suggests a very different function - the body of the ‘pin’ served as a handle for a pointer. The cross pin is not a hairpin or a dress pin - it is an aestel.

The Warminster Jewel, shown here on display in the Salisbury Museum, is the terminal or handle of an aestel, a manuscript pointer. It is made from a large, rock crystal bead enclosed in a gold mount. The socket would have held the pointer, a rod of wood or ivory. It dates from the late 9th century, contemporary with the Alfred Jewel. Both objects made use of 7th century crystal.

Two crystal beads from Breach Down, L49 and L50. These are smaller than the bead used for the Warminster Jewel, measuring 2.0 and 2.2 cm in diameter.

Four settings arranged around the central boss on a brooch will create as a cross pattern. Depending on its orientation the Breach Down brooch can be visualised as either a white or a red cross. The presence of a cross pattern doesn’t necessarily indicate that the jeweller intended to depict a Christian cross. Its burial in a Christian cemetery suggests that it was interpreted as such by its owner. There is a striking resemblance between the settings on the brooch and the shape of the cross on the cross pin - triangular garnets matching the expanded arms of the cross and white paste circles the hollows between the arms. The notches on the edges of the arms resemble the black niello triangles of the brooch’s inner rim and the corrugated outer rim.

The nearly identical brooches from Edix Hill, Barrington, Cambridgeshire and Bloodmoor Hill, Carlton Colville, Suffolk are close parallels to the Breach Down brooch. Both sites are 7th century cemeteries.

The gold disc pendant L17 is decorated with beaded wire filigree and gold granules and has a central cabochon garnet setting. Only 2.2 cm in diameter, the pendant is slightly smaller than a 10p coin. It has an overtly Christian design of a curvilinear cross with expanded arms, similar in appearance to the cross on the pin/aestel B1. It was made from an impure, pale gold reflecting the debasement during the 7th century of the Merovingian coinage which formed the jewellers’ main source of gold. The pendant was found in Barrow 1 along with one crystal bead (L49 or L50), 27 assorted beads (including the 22 beads catalogued as L54) and 18 amethyst beads (L53), the largest number of amethyst beads found in an Anglo-Saxon burial.

Elaborate circular gold pendants decorated with cloisonné settings and filigree became popular during the 7th century. The earlier examples, probably made during the first decades of the century, appear to derive their ornamentation from the contemporary composite disc brooches. As pendants developed away from the influence of the jewelled brooches, the use of cloisonné settings became far more restrained and filigree, which served as a space filler on the earlier pendants, came to be used as the principal decoration.

The gold disc pendant from the Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Sun Lane, New Alresford, Hampshire is a close parallel to the Breach Down pendant. The design lacks the central garnet setting, but retains the beaded collar. At the centre is a single bead of gold granulation, similar in appearance to the gold granules held within the loops at the ends of the S-scrolls on L17.

Rotating the New Alresford pendant by 45° changes the perception of the design from a plain cross with U-shaped arms to a cross with expanded arms decorated with filigree scrolls. The cross on the Breach Down pendant is practically overwhelmed by the profusion of filigree scrolls filling in the arms of the cross and the spaces between.

The gold disc pendant from Milton Regis, Kent presents another variation on the cross design. The composition is more closely related to the decoration used on the elite composite disc brooches. The cross sits within a frame and two of the arms are infilled with beaded wire filigree that imitates the shapes of cloisonné cells.

The disc pendant found during the excavations at St Mary’s Stadium, Southampton combines filigree panels with garnet cloisonné, surrounding a central cabochon garnet. Each of the four panels is decorated with Style II interlace in the form of a writhing snake, appearing to tie itself in a knot. The panels meet to create a cross pattern. The cloisonné cells and the filigree interlace are arranged symmetrically - the right side of the pendant is the mirror image of the left. The pendant shares features in its design and construction with two composite disc brooches from Milton, Oxfordshire.

Two nearly identical composite disc brooches were found at Milton, south of Abingdon in Oxfordshire. One is now in the Ashmolean Museum and the other, known as the Milton Jewel, is in the V&A. An examination of these two brooches and another similar brooch from West Hanney concluded that they were probably all made in the Upper Thames Valley. The Southampton pendant is a smaller and simpler piece of jewellery, but it is based on the same overall design - a cross with a ring of cloisonné cells at its centre and filigree Style II interlace between the arms. The pieces of gold foil in the bottom of the empty cells on the damaged brooch and the pendant are stamped with the same square grid pattern. The inner ring of cells on the pendant are 5-sided, interlocking with the wider cells of the outer ring. The cells are comparable to the more carefully shaped cloisonné cells on the brooches. Here double rows of 5-sided cells interlock to form the frame, cross arms and inner ring.

The brooch from West Hanney, 10 km west of Milton, differs from the Milton brooches in its design and construction, but it also uses a double row of 5-sided cloisonné cells to form its outer ring.

Only the wealthiest elite of Anglo-Saxon society would have been able to afford a composite disc brooch. Less wealthy women could display their status, and their Christianity, with a gold pendant. Milton is a short distance west of Dorchester-on-Thames. Cynegils, king of the Gewisse, was baptised there in 635, the first king of the West Saxons to be converted to Christianity. The grave-goods reflect the change of religion.

Above are two slides from a talk on the finds from a 7th-century burial given by Tania Dickinson to the Yorkshire Architectural and York Archaeological Society in January, 2022. The high-status burial at Acomb, west of York, included components from a composite disc brooch. The brooch was compared to the other related brooches with gold or copper-alloy cloisonné decoration. The dating of the brooches suggests links with the spread of Christianity during the 7th century.

Small, copper-alloy pendants were available for Christians who were unable to afford the expensive, cross-decorated jewellery. These little crosses, L77-L79, could have been worn on a necklace, but the presence of iron fragments in the suspension holes makes it more likely that these were suspended from a chatelaine. Such a use suggests that they functioned more as charms or amulets, offering the protection of the new religion, rather than as a public display of their owners’ Christian beliefs.

The wearing of chatelaines was a popular fashion in Kent which spread to other parts of England in the 7th century. L84 is a fairly complete chatelaine consisting of a suspension plate and ornaments and links of a chain, all made of copper alloy. They were cast and then decorated with punched ring-and-dot motifs. The ornaments would have been suspended on chains made up of alternating iron and copper-alloy figure-of-eight loops.

The gold bracteate M4 was made by pressing a sheet of gold over the obverse of a Roman coin of Maximinus I, known as Maximinus Thrax, (235 - 238 AD). It shows a bust of the emperor and the surrounding legend IMP MAXIMINUS PIUS AUG. With a diameter of 2.0 cm, the coin used to make the repoussé disc must have been a silver denarius. The bracteate is a relatively inexpensive imitation of a type of pendant made from a Continental gold coin that was popular in the 7th century. The addition of a gold suspension loop transformed a coin into an ornament that could be added to a necklace. The thin gold disc of M4 required a smaller amount of gold. It was found in Barrow 93 along with seven beads.

Coins could be used as pendants displaying either the obverse or the reverse. In many cases the coins chosen for pendants were decorated with a cross on the reverse. If they were worn with this side displayed they would obviously be regarded as symbols of their owners’ Christianity. However, the loop is usually positioned so that the bust on the obverse would appear upright, even though this resulted in the cross on the reverse appearing upside down. The representation of a ruler appears to have had a Christian significance. The coin pendant M4 imitates those coin pendants that were intended to be worn with the obverse visible, the right way up. Gold coin pendants continued to be made well into the second half of the 7th century.

A collection of looped coin pendants and other ornaments was found in the churchyard of Saint Martin’s in Canterbury sometime before 1844. The use of debased gold for some of the suspension loops indicates that the pendants came from more than one burial. Their owners must have been Christians. The church was used as a chapel by Queen Bertha, the Christian Frankish wife of King Æthelberht (560-616). From 597 it served as the base for St Augustine on his mission to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. The pendants were illustrated by Charles Roach Smith in 1848 in Collectanea Antiqua.

One of the pendants from St Martin’s is known as the Liudhard medalet. On the obverse is a bust of Bishop Liudhard who came to Kent with Queen Bertha to serve as her chaplain. The cross on the reverse has two bars, the lower one with a circle at its centre. The coin was made in Kent, possibly intended for use as a medal for a Christian convert rather than currency. The Breach Down bracteate M4 resembles the obverse with the bust and inscription.

The four coin pendants on a necklace from Sarre in Kent are mounted to display the emperor while the crosses on the reverse are upside down. The illustration is from a letter by Charles Roach Smith published in Archaeologia Cantiana in 1860. The emperor is also shown on the cloisonné bordered coin pendants from Bacton, Norfolk and Forsbrook, Staffordshire.

Linked pin sets, consisting of a pair of pins joined by a length of chain, were a fashionable accessory that appeared in the 7th century. The widespread popularity of this form of dress fastener is demonstrated by their discovery in cemeteries in many areas of Anglo-Saxon England. Sets were made of copper alloy, silver, and gold, the richest examples decorated with garnets. The Breach Down linked pin set L15 belongs to the lower end of the range, made of copper alloy with rather plain pins and simple figure-of-eight loops in contrast with the more elegant folded loops commonly used on pin sets. Linked pins were worn at the neck, possibly to fasten a veil - they are too delicate to have been used on a cloak.

The silver linked pins with garnet settings from Grave 39 at Chamberlains Barn, Leighton Buzzard had been used to fasten two layers of a fine fabric. A similar set of silver linked pins, lacking the garnets, was found in Grave 8 in the cemetery at Winnall, east of Winchester. The linked pin set from Cook Street, Southampton Grave 2962 was made from copper alloy and had figure-of-eight chain links.

Beads

The collection of finds from Breach Down includes a large number of beads made from a variety of materials and in a wide range of colours. The majority of the beads cannot be assigned to a particular burial. Beads from multiple graves are likely to have been strung together for convenience or to make an attractive display.

This group of sixty beads (L96) is made up of beads of green, blue and turquoise semi-translucent glass; brick red and yellow opaque glass; one spiral of blue glass; one of green and one of blue transparent glass; one triple, one double, and one single fluted bead of blue glass; one quoit-shaped of blue glass with a white spiral trail; six made of a white, chalky material and three amethyst beads. A disc of polished dark brown stone drilled with two holes from edge to edge might have been used on a necklace strung with a double thread.

Beads were recorded in ten of the eighty-two barrows opened by Conyngham. Three burials contained only one bead, a blue and white trailed bead (L51) in Barrow 5, a crystal bead (L49 or L50) in Barrow 47, and a small green glass bead in Barrow 6. Two beads were recorded in Barrow 35. A child was buried in Barrow 67 along with ‘beads of various colours’ and ‘toys, the evident offerings of parental affection'. The eight beads found in Barrow 81 were listed as: 1 green, 3 red and 1 small yellow of 'vitrified clay' (probably opaque glass); 1 spiral of green glass; 1 amethyst; 1 small bone bead. These were found at the neck and chest along with a pin with a flattened head.

Larger number of beads would have been threaded up, sometimes along with twisted wire rings, to make short necklaces. There were seven beads (M6) in Barrow 99 and seven beads (M5) and a gold bracteate (M4) in Barrow 93. The cross pin burial in Barrow 103 had five beads (B27) and two wire rings (B14 & B16), and in Barrow 58 an unspecified number of beads were strung up along with three wire rings (L23-25). The woman in Barrow 69 was buried with ‘a number’ of small star-shaped beads and one larger bead. Twelve very small beads (L56) were found in Barrow 53 along with the large triangular buckle (L14) and the keystone garnet disc brooch (L16). These seem to be unsuitable for a necklace and might have been sewn onto the woman’s clothes. There were said to be about twenty beads (J1) in Barrow 101, but the record for the largest number from the site is held by the wealthy woman in Barrow 1. Found near the neck were one crystal bead, eighteen amethyst beads, twenty seven assorted beads (L54) and the gold disc pendant (L17).

John Akerman’s 1855 illustration of the amethyst necklace, crystal bead and gold pendant found in Barrow 1.

Beads found with the amethyst necklace.

Wire rings with carefully twisted ends were threaded together with beads to make necklaces. The rings from Breach Down are all made of silver. On two incomplete rings, one end of the wire has been twisted back on itself to form a loop. The missing terminals might have been shaped into a hook - a hook-and-eye fastening would allow the rings to be opened and closed.

Silver wire rings -

Row 1: L67, L23, L68, L25

Row 2: L24, L69, L70, L71

Four of the seven beads (M6) found by Mantell in Barrow 99 are in the British Museum - the two loose beads and the two striped beads. The other beads (M5) were found with the gold bracteate in Barrow 93.

Glass beads (B25) in the collection of finds by Rev JP Bartlett. The group includes a quoit-shaped bead with a white spiral trail and an unusual oblong bead, rectangular in section with two lengthwise holes.

The glass beads display a variety of colours. In some cases the colouring would have been unintentional - iron was often present as an impurity, tinting the glass green or yellow/ brown. The glassmakers had more difficulty making a clear glass than a coloured one. Deep shades were made by the addition of colourants. Some colours would have been relatively easy to manufacture using readily available materials. Iron oxide would have been used for brick red glass and copper compounds for turquoise and green. Tin oxide would make an opaque white glass and could have been added as an opacifier in coloured glass. Orange and yellow were more difficult to produce, perhaps coloured with antimony, so these colours are likely to have been more expensive and highly prized. The collection shows a definite preference for strongly coloured opaque or semi-translucent glass beads. The most popular colours were brick red made from opaque glass, a rich deep green of slightly translucent glass and turquoise beads varying in shade and opacity.

Most beads are a simple shape - barrel is the most common with smaller numbers of ring, quoit and truncated bicone. The shapes of the beads are related to the method of manufacture. The translucent glass rings were made by spinning a lump of molten glass on a metal rod, giving the beads their rounded, doughnut shape. Spiral striations on many of the opaque beads suggest they were made by winding a cane of glass, softened by heating, around a metal rod. Some beads might have been made from glass frit, ground and made into a paste and then moulded into shape.

Necklaces of amber beads were a popular fashion in the 6th century. Amber beads continued in use into the 7th century, but are found in burials in much smaller numbers. This group of beads (L55) includes six amber beads that are roughly barrel shaped and cut flat at either end.

These twelve beads (B26) had been mounted together on a card when the Bartlett collection was purchased by the British Museum. They could have been found in more than one grave. Along with the common monochrome glass beads are one irregularly shaped amber bead, a long cylindrical bead and a narrow glass spiral. A small bead is decorated with stripes in opaque white and clear purple glass. The other small bead is bright red and translucent. It has a lentoid cross-section resembling that of an amethyst drop-shaped bead, but on a much smaller scale. It might be made of garnet.

The amethyst bead necklace from Barrow 1. One of the large beads, shown with a crack across the centre in Akerman’s 1855 illustration, has been lost.

Two of the beads found with the cross pin in Barrow 103 are drop-shaped amethyst.

Amethyst beads became popular in the 7th century. They are usually found singly or in pairs, probably a reflection of the high cost of these exotic imports. The necklace (L53) from Breach Down with eighteen beads is one of the largest collections of amethyst beads from a single grave. Five are large drop-shaped beads 4.1 to 4.7 cm in length - one other similar, broken bead has been lost. The smaller beads are 1.3 to 2.3 cm long. In contrast to this exceptional burial, the other 100+ barrows excavated on the site produced only a handful of amethyst beads. A group of sixty beads (L96) that were probably found at Breach Down includes three small to medium sized amethyst beads. One of seven beads (M6) in Barrow 99 and two of five beads (B27) in Barrow 103 were amethyst.

The grave-goods in Barrow 34 were recorded as a small buckle, iron fittings of a wooden box and three halves of large amethyst beads (L52). Two of the halves fit together - the original bead had been about 4 cm in length. It has been cut from two sides, with a broad cut near the edges and a narrower cut across the centre. One of the half-beads has a shallow second hole on the cut next to the hole running through it. When the bead had been manufactured, the holes drilled from either end did not meet. The bead was cut where the holes overlapped. The error in drilling the bead explains why it was cut in half - it couldn’t be strung on a necklace without a hole running from end to end.

The half-beads provide an interesting insight into the trade in amethyst beads. The beads were newly manufactured, not secondhand ornaments removed from Byzantine jewellery. They had arrived in Kent loose, not strung up into necklaces. The beads in the Breach Down necklace were graded in size and must have been selected from a larger collection. The faulty beads were roughly cut with the ends left unpolished. The Saxons did not have the skills required to re-drill or rework the amethyst.

Further Reading

Anglo-Saxon Beads 400 - 700 AD - A Visual Guide to Types and Techniques by Sue Header, 2025.

Pottery

The grave-goods in four of the eighty-two barrows opened by Conyngham included a ceramic pot. Three were illustrated in his 1844 account of the excavations. Of these, the globular urn with an upright rim, probably a handmade pot, wasn’t included in the collection purchased by the British Museum. Sherds of 'unbaked or very slightly baked clay' were recorded in Barrow 81, but were either left in the ground or lost. Mantell illustrated two pottery vessels found in 1810, neither of which has survived. All but one of the six pots were found at the foot of the grave.

The two surviving pots from Breach Down are both examples of imported Frankish wheel-made pottery. Pot L47 is a biconical bowl with a vertical rim. The upper half of the pot below the rim was decorated on the wheel with a broad roulette with a zigzag pattern. After the pot had dried to a leather-hard state, grooves or flutes were cut into the upper and lower body, largely obscuring the zigzag rouletting.

Pot L46 is a tall biconical bowl with horizontal grooves and ridges on the upper part of the body and a slightly everted rim. It was found in a well furnished male burial, placed at the head of the grave and apparently used as a cremation urn.

Barrow 33. Skeleton almost entirely decayed.

1. Sword two feet six inches long, placed on three large stones.

2. Four small buckles, lying about the middle of the sword blade.

3. Shield boss (L105 or 106).

4. Spearhead, by side of skull.

5. Two glass studs, at the centre of the body.

6. Pot (L46) containing calcined bones, at the head.

Cremation burials are relatively uncommon in the 7th century. A cremation was found in the churchyard at Pagham, West Sussex. The high-status burial in the barrow at Asthall, Oxfordshire was a cremation. The grave-goods included a drinking horn and an imported wheel-made bottle with roulette decoration. The combination of an inhumation and a cremation in Barrow 33 seems to be unique.

Conyngham’s 1844 illustration of the shield bosses (L105 & L106) found in Barrow 2 and Barrow 33.